Features

Business

Contractor at Work

Drainage Management Systems

Celebrating 50 years

The evolution of the drainage industry and the publication that covers it

May 23, 2023 By Bree Rody

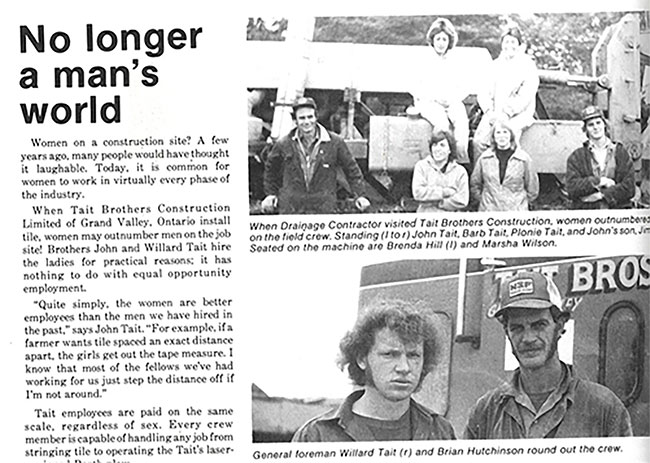

A 1970s issue highlights female involvement in the industry.

A 1970s issue highlights female involvement in the industry. The practice of subsurface drainage for agricultural purposes has been around some 202 years. First introduced to the world by John Johnston, a Scottish immigrant readying his farm in the Finger Lakes region.

When Johnston’s first barley crop failed, Johnston defied advice to simply move somewhere else to find better land that drained naturally. Instead, he set out to improve his soil. So came the arrival of subsurface drainage – first in the form of clay and then, more than a century later, in the form of plastic.

It was not just the growth of drainage as a business but also the innovation in the drainage industry that prompted the launch of Drainage Contractor 50 years ago, says Peter Darbishire.

“It was the perfect storm of things happening all at once,” says Darbishire, the former co-owner and longtime editor of Drainage Contractor. The drainage industry of the late 1960s, he explains, was in a period of fast-paced change. When corrugated plastic pipe was introduced in both the U.S. and Canada, that was driven by high demand for pipe. “There wasn’t enough clay or concrete pipe out there. [For] contractors, their biggest stumbling block was, how much pipe could they get?”

This prompted the establishment of a number of plastic drain pipe manufacturing companies such as Big ‘O’ in Canada, followed by U.S. companies including ADS and others. At the same time, both the modern drainage plow and laser technology to control grade was introduced. Also during that period, researchers in the U.S. and Canada were working hard and fast on projects relevant to the industry. What the industry lacked, says Darbishire, was a national media and communications platform for education and awareness.

It started with a newsletter, says Darbishire, one put together by a former advertising agency working with Big O. “At the time, it was Ontario-only,” he says. But demand from contractors and industry suppliers on both sides of the 49th parallel led to the inception of what would eventually become Drainage Contractor Magazine.

Now celebrating 50 years of publishing, Drainage Contractor continues to publish two print issues annually, while also engaging in multiplatform media such as podcasts, webinars and eNewsletters, as well as an annual GroundBreakers recognition program.

While drainage plows and laser technologies were all the rage when Drainage Contractor first hit the presses, today, drainage is at an intersection of complex challenges – including environmental and bureaucratic challenges – and tremendous opportunity and innovation. Together with some of the industry’s influential voices, we look back – and forward.

Growing the brand

When Darbishire joined the brand, he came on as technical editor because he had a background in lasers, working as an applications engineer with Laserplane Corporation prior to his move to Canada. He also had a background in agriculture, so the magazine was “really in my bailiwick.”

Like the industry itself, the magazine was experiencing skyrocketing growth at the time. Initially an annual, Darbishire says it went from a few dozen pages in its first year to around 68 pages in its second. “The next year, it was a perfect-bound 200 [pages].” He recalls the peak production being around 1977, when the company produced a 278-page issue, with “massive inserts” of around six to seven pages each. For several years, there was also a European edition, which Darbishire said was born from a similar issue to that in North America – “They just didn’t have any general communications in the industry.” Darbishire also acknowledges that drainage is “such a specialized area that it would be difficult to start it now, because things are so different in communications.” While today’s highly digitized and social media-driven landscape make it easy to communicate product launches and share demonstrations, at the time, he says, “All of these new technologies and techniques and machineries were coming out so fast, to get the word out there was difficult.”

Eventually, he and business partner Peter Phillips sold AIS Communications, the company that produced Drainage Contractor and five other B2B titles, to Annex Business Media (then Annex Printing & Publishing) in October 2004. Along with Drainage Contractor came other titles which are still operating today: both regional editions of Top Crop Manager, Gound Water Canada, Glass Canada and Canadian Rental Service.

The biggest recurring issues that Darbishire found himself covering in those early days as technical editor and, eventually, editor, mostly revolved around machinery and a quest for efficiency. “The machinery was being developed very quickly,” he says. “Up until about the late 60s, the majority of pipe in north America was put in with wheel trenchers. Those machines were maybe 60 to 80 horsepower. The companies producing those machines [steadily] increased the horsepower and increased the productivity of those machines. At the same time, European manufacturers came in with trenchers with much more power and speed as well. And lasers helped contractors to maintain grade and design systems more efficiently in the field. “Let’s say you go from a machine that can go at 20 feet per minute, to a machine that can go 50 per minute. The logistics on the field change because suddenly, ‘oh, I haven’t got enough pipe!’ And if the trencher’s not running, it’s not making money, so that increased the pressure contractors to increase their field efficiency. That was something we’d talk about in the magazine. The thing is, everyone was so eager to share their experiences and ideas for improvement, there was plenty of editorial content available!”

Intense innovation

Clark Farm Drainage president and LICA past president Bob Clark II agrees that the quest for productivity has continually driven some of the biggest advances in drainage. For example, says Clark, the laser grade systems that were in their infancy when Darbishire joined Drainage Contractor would eventually go on to be largely replaced by real-time kinematics, or RTK-GPS machine control. Those, along with geographic information system (GIS) software “dramatically improved productivity,” according to Clark.

Ehsan Ghane, assistant professor and extension specialist at Michigan State University, goes even further – he believes software has been the biggest game-changer in drainage, period. Academia and extension, as well as private companies, have been hard at work over the last several decades developing software for all levels of data. Ghane says there are still different types of people who might install drainage, and thus, the software can’t be one-size fits all.

“There are two groups of people who are going to design a drainage system,” says Ghane. “One are people who might be using small tools for a simple job, just a few farms.” While there are often farmers who choose to install their own drainage, Ghane says that doesn’t mean they want to do it as a career. There are smaller, specific and often even free tools to aid in the design, such as mapping technology. For those who are in the tiling business, Ghane says, they’re more likely to make investments in advanced software, which is often subscription-based. “These systems are making a big difference in how fast one can generate a design,” he says. His team at Michigan State developed a drain spacing tool in 2021 which is equally useful to both the DIY tilers and the professional drainage businesses.

It’s a far cry from the early days of drainage. In John Johnston’s day, according to Geneva Historical Society curator of collections John Marks, no one kept maps of their tile – infrared aerial images still show Johnston’s original tile lines. By contrast, Clark says GPS-based technology has been among the biggest game-changers in all facets of drainage. This includes yield maps, which Clark says “allowed landowners to better manage capital improvements to agricultural lands.”

A maturing industry (and magazine)

As a practice, drainage has been considered a miracle by some, but a problem by others – and it’s impossible to say drainage hasn’t been without its controversies. Increased scrutiny on the issue of nutrients leaching into waterways has caused many researchers and activists to zero in on agricultural drainage as an obvious source of nutrient transport.

All of this is ironic, says the University of Illinois’ Laura Christianson, considering the very roots of drainage. “Tile drainage used to be considered a conservation practice,” she says. “The roots of conservation go all the way back to the start of tile drainage.”

Clark echoes that there’s an opportunity for drainage – and challenge – as populations grow. There’s greater demand “for food, fuel and fibre,” and thus a greater demand for agricultural drainage. All the while, climate continues to become more variable and volatile, posing a challenge.

Despite rhetoric about drainage that can be divisive at times, most experts agree that crops grow best on well-drained land. The key is not to eliminate drainage, but rather to design better drainage systems.

Christianson agrees that these challenges in drainage are also an opportunity to innovate, and these innovations have been predominant since the turn of the millennia. “As conservation has really grown form the early 2000s to where we are here in 2023, what we’ve really focused on is reducing nitrate loss and phosphorus loss with conservation ideas,” says Christianson, who has focused a great deal of her research on saturated buffers and woodchip bioreactors. It’s fair to say that adoption is slow, she says, which is in part because despite their benefits, they provide no yield benefit and thus aren’t a moneymaker. “I feel like there’s a lot of education we can provide to contractors, because they don’t view bioreactors as something to market to clients… It’s just an extra cost.”

She credits partners such as Illinois LICA and the Iowa “Batch and Build” program for raising awareness and adoption. The efforts are the result of collaboration between farmers, landowners, farm organizations, governments (including the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship) and other stakeholders to expand and scale up the deployment of bioreactors and other proven soil conservation practices, while also offering cost-share. “It’s increasing,” says Christianson. “We’ve only really been doing bioreactors for 10, 15 years. You have to grow. [The Batch and Build program] really gets the economy of scale for full engineering firms, as well as drainage contractors. She adds that for landowners considering upgrading their drainage system, it’s the perfect time to invest in a bioreactor. “Every bioreactor is a win.”

Other common practices that fall under the drainage water management (DWM) umbrella include controlled drainage, drainage water recycling, phosphorus removal structures, edge-of-field practices and more. Christianson says she’s particularly excited about the opportunities that come from drainage water recycling, both from an environmental perspective and an economic one.

“It’s all about managing risk,” says Christianson, who believes that 100 years from now, many drainage systems could be combined with drainage water recycling systems. “We manage wet conditions well, but I believe the problems of drought and dry conditions will only increase in the Midwest. I think it’s a crisis, but it’s a huge opportunity to rethink how we manage water.”

For Clark, better management and design of DWM systems will be key. “With better system management I could foresee better yield optimization, better nutrient management, improved carbon sequestration and overall soil health.”

The more things change

While the drainage industry is evolving at an overwhelming pace in terms of technology and priorities, some things never change. It’s still considered a tight-knit and highly sociable industry, with annual events such as the LICA National Summer Meeting drawing contractors from around the continent, or last year’s International Drainage Symposium bringing together contractors, landowners and researchers from around the globe to discuss advances in drainage.

For Darbishire, he’s an honorary life member of the Land Improvement Contractors of Ontario. He says it’s about more than just going to the events because he gets a free pass. “I go and try to contribute something.” He adds that when he’s out for a drive, if he sees a crew installing tile, he doesn’t hesitate to get out and talk to the team. “I have this ingrained interest in the industry,” he says. DC

Print this page