Features

Contractor at Work

The value of tile maps

How to map older, existing tile drainage systems.

June 11, 2020 By Steve Hoffman

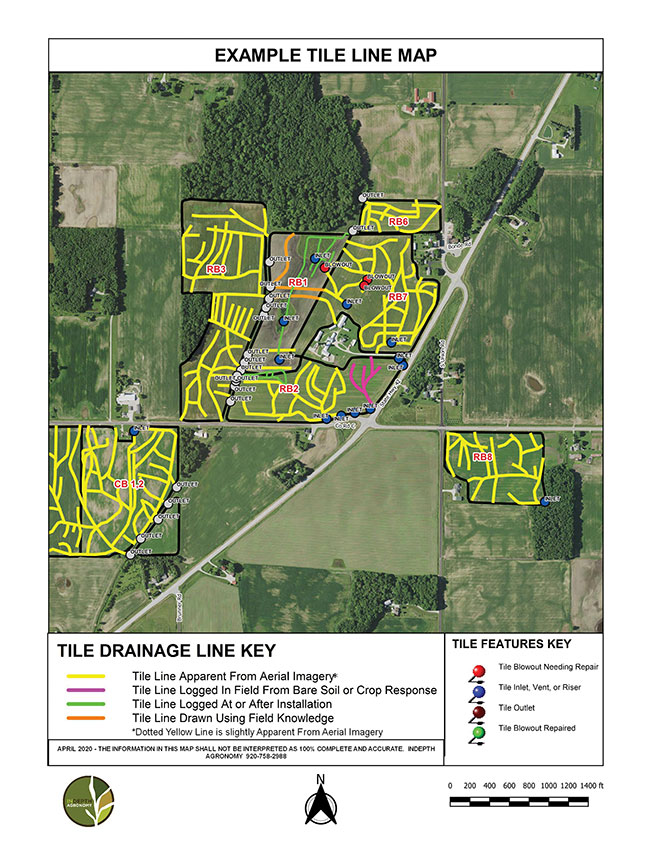

By using multiple georeferenced air photos in a GIS program such as QGIS, one can usually piece together a decent map of tile systems in a field by drawing in apparent lines using as many good images as possible. Photo courtesy of Steve Hoffman.

By using multiple georeferenced air photos in a GIS program such as QGIS, one can usually piece together a decent map of tile systems in a field by drawing in apparent lines using as many good images as possible. Photo courtesy of Steve Hoffman. The agronomic value of tile drainage has never been more obvious. It is not unusual for farms to have a mix of newly grid-tiled fields along with fields that were pattern tiled 40 to 70 years ago.

Unfortunately, GPS mapping of tile systems at the time of installation was not a widely used option until relatively recently.

There are many reasons to have a good map of each field’s tile system. It is important to know the location of inlets, vents and outlets when manure is applied to a tile drained field. Nutrient management plans require a setback or an immediate incorporation zone around tile inlets and vents. Outlets require monitoring during and after manure application. If you have ever stumbled through tall grass for the length of a ditch looking for an unmarked tile outlet, you will recognize the value of a good tile system map.

Clay and concrete section tile systems that were installed 40 plus years ago have been showing their age for quite a while now. Tile blowouts and suck holes are a hazard to surface water quality during and after manure application. With a good tile map, it is relatively quick and easy to check for tile blowouts. If a new grid tile system is on the wish list but not affordable right now, it might be practical to improve the existing system by adding a branch line. Having a map of the existing tile drainage system is very helpful when planning an upgrade.

The “jigsaw puzzle” mapping method

So how can we come up with decent tile drainage system maps for older, existing systems? The only practical option I know of to develop a map for those systems is the “jigsaw puzzle” method. By using multiple georeferenced air photos in a GIS program such as QGIS, one can usually piece together a decent map of tile systems in a field by drawing in apparent lines using as many good images as possible. These aerial images are available from governmental agencies such as the National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP) as well as from mapping apps such as Google Earth and Bing Maps.

By using multiple georeferenced air photos in a GIS program such as QGIS, one can usually piece together a decent map of tile systems in a field by drawing in apparent lines using as many good images as possible.

Several aerial imagery services offer multi-flight packages spaced out through the growing season. A well-timed bare soil image as the soil begins to dry in spring usually provides a very good picture of the drain tile locations. Aerial imagery can also be useful in-season when excessive rainfall occurs over an extended period. The excessive rainfall causes stunting of the crop, while areas over the tile lines are taller and greener. Improved crop growth over tile lines can also be seen during an exceptional drought. I have even seen some high-resolution satellite imagery that clearly showed drainage lines in a field.

As imagery options become more numerous it will be easier to put together the puzzle in a shorter period of time. High resolution satellite companies are starting to offer “a la carte” purchases of imagery that allow you to preview historical images to see which ones fit your need before purchasing the image. I have not found it possible to develop drainage system maps in fields that have a permanent vegetation cover.

It is very useful to provide a copy of the preliminary map to the farmer or landowner. I make it clear that the lines that have been drawn look like they could be drainage lines, but they also might be other temporary features such as a travel lane, ephemeral gully erosion, etc. I ask the farmer or landowner to cross off the lines they know are not drainage features and also to hand draw missing lines they know exist. The maps should use color-coded lines base on the evidence used to create them – logged during installation, apparent from imagery, logged from crop response or dry soil lines, or based on field knowledge of the drainage system. It is also helpful to have the farmer or landowner mark the location of all known outlets, inlets and vents.

I ask the farmer or landowner to cross off the lines they know are not drainage features and also to hand draw missing lines they know exist.

The next step in developing a drainage system map is ground truthing. Springtime, before tillage occurs, is a great time to ground truth the drainage feature map. The perimeter of a field can be driven with an ATV before vegetation regrowth occurs to look for inlets, outlets and vents. Features that have not already been mapped can easily be logged with one of many available GPS devices or apps. This is also a good time to drive the lines looking for blowouts and suck holes that may have developed in no-till situations. Apparent lines can be followed to the ditch to confirm the location and condition of the outlet. Georeferenced photos of tile features can be a useful tool to remind us of components that need maintenance. If you are using a full featured GIS program to develop the drainage features map, you should consider adding attribute information such as such as date of installation, tile diameter and material, and direction of flow.

A map is only useful if it is available when needed.

A map is only useful if it is available when needed. Maps that are stored in a Cloud system can be accessed on smart phones and tablet computers. These devices can run apps that allow you to record new features as field activities are performed. Google Earth is a useful app that can show a “live” GPS map of tile features that can be used in the field.

Like all maps, a drainage feature map should never be considered to be 100 percent complete. It is meant to be a living document that will need to be updated as previously unknown features are discovered or new ones are installed.

Steve Hoffman is the president and managing agronomist of InDepth Agronomy, an independent agronomy business located in Wisconsin. He is a certified CPAg, CPCC-I and has been developing drainage system maps for his clients since 2008.

Print this page