News

Lessons learned

Ten things you may not have known about drainage.

November 4, 2013 By Stefanie Croley

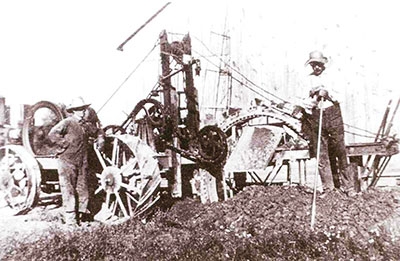

Drainage contractors Will Forrest and Art Goslin in a 1917 photo. Attendees of the 2013 LICO and DSAO Drainage Convention

Drainage contractors Will Forrest and Art Goslin in a 1917 photo. Attendees of the 2013 LICO and DSAO Drainage ConventionAttendees of the 2013 LICO and DSAO Drainage Convention, which took place in January in London, Ont., saw several speakers and presentations offering tricks of the trade.

One such presentation that caught the eye of Drainage Contractor magazine was by Sid Vander Veen, drainage co-ordinator with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food. It was entitled 10 Things You Did Not Know About Drainage.

In a room full of industry professionals, Vander Veen’s presentation was bravely named, but as he explained, the presentation was originally intended for a different audience. “I am Canadian, and, therefore, I start out with an apology,” Vander Veen joked, explaining that his talk was originally given to a crowd of people involved in conservation and resource management. However, Vander Veen had several interesting facts about agricultural drainage to share with the folks in attendance at the LICO convention. In case you missed it, here’s a recap of Vander Veen’s 10 points.

10. Subsurface drainage functions comparably to the holes in the bottom of a flower pot.

Subsurface drainage drains the water out of the top layer of the soil, leaving the soil moist, but not saturated and drowning the crop roots. “Many in the resource management crowd view tile drainage as a bad practice,” Vander Veen explained. “I want to show that tile drainage functions no different than the holes in the bottom of a flower pot – it is a fundamental means of providing the proper growing conditions for crops.”

9. Subsurface drainage dates back as early as the second century B.C.

As Vander Veen explained, there has been a long-recognized need for subsurface drainage, and a huge increase in drainage in the late 1960s and early ’70s. But rolling the clock back even further, to the late 1800s and early 1900s, clay tile was installed with a wheel machine – a very labour-intensive process. “Each clay tile was individually put into a chute and laid at the bottom of the trench. The trench would then have to be backfilled . . . The practice of tile drainage was slower back then,” Vander Veen said.

In the early to mid-1800s, anything that could form a conduit where water could flow through, including rocks, chunks of wood or clay tile, was used for drainage. Tile drainage in North America was largely attributed to John Johnston, a Scottish immigrant to New York State who embraced drainage in 1835. Prior to Johnston, there were sporadic references to tile drainage: in France in the 1600s and in Scotland in the 1400s. Palladius, a Roman agriculture writer in the third or fourth century, wrote on drainage, and Lucius Columella wrote on agricultural drainage at the time of Christ. And the very earliest reference to drainage was Marcus Porcius Cato, 239-149 BC, who wrote that if the land is wet, it should be drained with trough shaped ditches. “It’s important to realize that subsurface drainage has been recognized as a necessary component of agriculture for a very long time,” Vander Veen said.

8. Subsurface drainage reduces the overland flow and the movement of sediment, and . . .

7. Subsurface drainage only flows when the water table rises to the bottom of the pipe.

These two points are directly related. When it rains, tile drainage increases the capacity of the soil to absorb water, which allows the soil to function almost like an urban storm water management pond. As Vander Veen noted, many people know that storm water management ponds are installed to slow down water runoff. “Tile drainage does the exact same thing, using the agricultural soil surface as the storage area,” he noted. “The fact that tile drainage encourages more water to go down is good. When it stops raining, tile are still flowing, and the tile are now doing their job of getting that root zone of the crops in a good condition so that it doesn’t drown the crops.”

6. Subsurface drainage acts as a conduit for water – it does not pollute water.

Vander Veen asked the audience how much air pollution an empty road causes regularly. The answer was zero. He then asked how much air pollution a road with lots of traffic on it causes regularly. The answer was, again, zero. “The cars are creating air pollution, and the road is the conduit for the cars, but the road itself doesn’t create any air pollution,” he explained. “So often, when we look at tile drainage, I hear claims that tile drainage pollutes. It doesn’t – but it can be a conduit for pollution, and we need to continue to work on land management practices to try to minimize that.”

5. Subsurface drainage encourages crops to develop stronger root systems, which help them in dry conditions.

High water levels in the soil tend to cause crops to develop a shallow root system. When dry conditions develop, the crops with the shallow root system are usually the first to suffer. Tile drainage lowers the water level in the crop root zone, which encourages crops to develop healthy, deeper root systems in the soil. These more extensive roots allow these crops to better withstand dry conditions. Tile drainage contractors know that even in dry conditions you see where the tile runs are in the field because the crops are actually better immediately over the tile. Tile drainage improves crop production and crop yield in dry times as well.

4. Ontario is one of the few jurisdictions in the world that require tile drainage contractors to be licensed.

In Ontario, the Agricultural Tile Drainage Installation Act is in place to protect farmers by regulating contractor workmanship. The Act applies to the installation of tile drainage systems on agricultural land only, and licenses are not required when an individual installs tile drainage on their own land using their own tile drainage machine. A business license, a machine license and a machine operator license are all required, and operators must successfully complete a five-day primary drainage course and an eight-day advanced drainage course. As Vander Veen said, this is not necessarily the case around the rest of the world.

3. There are benefits to subsurface drainage that extend beyond increased crop productivity.

There are several benefits of subsurface drainage to farmers besides increased crop productivity, Vander Veen explained. “Improved trafficability is one. Drainage reduces the fuel consumption when working the land.” Tile drainage allows farmers to take advantage of optimal planting times. And finally, environmentally conscious methods of farming, like no till and conservation tillage practices, depend on well-drained land to be effective, he pointed out.

2. Subsurface drainage improves crop productivity, which reduces pressure on land conversion and improves our ability to produce food for a growing population.

As Vander Veen pointed out, the world’s population is continuing to increase, and we’re running out of space for everyone. “We’re not making new agricultural land – and we’re building on what we have,” he said. “There are extra pressures on our agricultural production capability like biofuel production and loss of prime agricultural land due to urban development. These are all good, important things, but at the end of it all, we still have to produce food. How do we do that for a growing population?” His solution is to try to improve production with what land we have using soil moisture management, a combination of drainage and irrigation. “To me, that’s the least intrusive and one of the best ways of trying to continue to improve our food production capabilities.”

1. Conservation goals can coexist with agriculture and subsurface drainage.

Jack Miner was a world-renowned naturalist who was awarded the Order of the British Empire in 1943 for the greatest achievement in conservation in the British Empire. Miner was born in the United States and his family moved to Canada where his father worked as a clay tile manufacturer. “To make the tile, clay was removed from the ground, which created pits,” Vander Veen explained. “The pits filled up with water and they became some of the very first geese sanctuaries.” During the time that Miner was getting recognition as a world-renowned conservationist, he continued to make drainage tile. He recognized the balance between agriculture drainage and conservation and resource management. Before ending his presentation, Vander Veen recited one of Miner’s poems, which, with verses like the one below, was a hit with the audience.

- If your land is too wet and you’re burdened with debt

- And encumbrance begins to accrue,

- Obey Nature’s laws, by removing the cause,

- Drain your farm or it will drain you.

Print this page