Features

Drainage Management Systems

Nutrient loss in Illinois

How drainage contractors can help.

May 23, 2017 By Julienne Isaacs

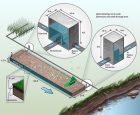

A research woodchip bioreactor is installed to remove nitrate from a tile drainage system at a farm in Illinois. Since 2011

A research woodchip bioreactor is installed to remove nitrate from a tile drainage system at a farm in Illinois. Since 2011Since 2011, the majority of corn producers in Illinois have followed the recommended maximum return to nitrogen (MRN) application guidelines. More than half of all farmers are either knowledgeable or very knowledgeable about the “4R” strategy (right nutrient source at the right rate, in the right place and at the right time).

But 43 percent of those producers have no knowledge of denitrifying bioreactors or how they can function to improve water quality. Only 55 percent claim knowledge of drainage water management.

These are some of the results of the Illinois Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy (NLRS) Practice Implementation Survey, released by the United States Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) in collaboration with the Illinois Nutrient Research and Education Council, Illinois Farm Bureau, and Illinois Extension this past December – and they reveal some key opportunities for drainage contractors in the state.

“There are a lot of good contractors who are engaged with conservation drainage practices and interested in learning more,” says Laura Christianson, an assistant professor of water quality at the University of Illinois. “But there are a lot of guys installing tile on the fly and they may not know about some of these new practices.”

“Honestly, if you’re a contractor and you understand them, that’s a marketable opportunity.”

Illinois’ NLRS survey was intended to measure in-field and edge-of-field practices conducted by Illinois farmers as they relate to nutrient loss reduction.

According to Mark Schleusener, state statistician with the United States Department of Agriculture, the NLRS is a plan primarily formulated by the Illinois Department of Agriculture and other groups to deal with the fact that nitrogen and phosphorous don’t stay in the state’s soils. “They pass out through leaching and soil erosion, getting into the lakes, streams and rivers, and then down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico,” he says.

The Environmental Protection Agency has tasked 12 states with reducing runoff from agricultural fields and urban areas via state-developed plans tailored to local conditions and farming practices.

Schleusener, with assistance from Christianson, helped develop the survey, which was distributed in July 2016 to measure producers’ progress between 2011 and 2015.

Though the response rate isn’t public, Schleusener says the most significant survey results did, in fact, reveal improvements. “Some of the things producers are doing voluntarily are helping to reduce nutrient losses,” he says.

Opportunities for drainage contractors

But it’s the areas in which Illinois producers have room to grow – edge-of-field practices such as building constructed wetlands and installing denitrifying wood chip bioreactors – where contractors can help drive further progress, Christianson says.

Other states, like Iowa, have officially approved more practices, such as drainage water management, shallow drainage and saturated buffers, but Illinois is still collecting data on how well these practices perform in the state. Until Christianson’s research team and other researchers in the state can feel confident recommending further drainage practices, constructed wetlands and bioreactors remain the only two, beyond tile installation, that contractors are involved in in the state.

“In Illinois, we do have some folks putting in bioreactors and constructed wetlands, but there is a huge opportunity to do more,” she says. “On our survey, there were so few bioreactors reported that they couldn’t report results. Forty-three percent of the respondents had no knowledge of a bioreactor, so it’s a big opportunity for education.”

Drainage contractors who familiarize themselves with bioreactors and how to install them will be ahead of the curve when nutrient loss starts coming under the gun in the state, she says.

The same goes for constructed wetlands, which require skilled earthwork to incorporate them into the landscape.

But Christianson sees another opportunity for drainage contractors. Controlled drainage may not be a recommended practice in Illinois right now, but Christianson’s research team is seriously evaluating it for future inclusion.

“One of the challenges I’ve come across is that it seems as though there are a lot of crop advisors, farmers and contractors who feel they are doing drainage water management, but in reality there are very, very few acres where it’s being done in Illinois,” she says.

She pegs this to widespread misconceptions about how drainage water management actually works.

“If you have tile drains you might think that you’re managing drainage water, but the practice involves having control structures, and not just having the structures, but managing them,” she says. “There are educational opportunities there.”

Producers can be leery of adopting edge-of-field practices as opposed to in-field practices that have other production or yield benefits, but Christianson says not enough producers and contractors are aware that there can also be yield benefits to retaining drainage water via control structures.

Drainage contractors are a “prime audience” for Christianson’s research, she says, and contractors are increasingly at the table when it comes to discussions about Illinois’ nutrient strategy.

“We have loud agriculture voices in Illinois that are very politically connected in terms of our nutrient strategy, but more and more I’m seeing Illinois Land Improvement Contractors Association members coming to those meetings too to really engage,” she says. “They’re saying, ‘We have contractors out there that want to do the right thing’.”

The more contractors know about the options available to producers for nutrient loss reduction, the more ably they can work with producers to meet future targets and lead Illinois water management into the years to come.

Bioreactors and constructed wetlands

Tile drainage systems can sometimes accelerate or increase nutrient runoff from agricultural areas, but bioreactors and constructed wetlands can help.

Wood chip bioreactors are trenches filled with wood chips, through which tile water is allowed to flow before entering nearby bodies of water. Soil bacteria colonize the wood chips and break down nitrates in the water, minimizing nutrient runoff. Wood chips need replacement every seven to 10 years, but bioreactor structures last for up to 20 years.

Information on designing and constructing bioreactors can be found here.

Constructed wetlands are artificial wetlands that can treat or filter agricultural wastewater year-round via natural processes, before runoff reaches wider watersheds. In contrast with restored wetlands, constructed wetlands are installed in areas that may or may not have been wetlands in the past.

Information on siting, designing and building constructed wetlands can be found on the Environmental Protection Agency’s website.

Print this page